Originally published in Modulo magazine, 11th edition, page 26 (1958), this article has been translated by Patrick Finn. This is a facsimile reproduction of the original.

It’s fascinating to read an article written by one of the most important figures of Brazilian mid-century modern design, especially to see his own perspective. In this article, Sergio Rodrigues shares the transformation Brazil went through in the 50’s, how new materials opened up new opportunities to innovate architecture & furniture production, and his critique about craftsmanship and industrial processes. So, no more about it let Sergio Rodrigues speak for himself.

The history of furniture, like that of architecture, is closely linked with the expansion of industry, in this present century. Thus for instance, the introduction of iron reinforcement into concrete, forming ferro-concrete — plastic material — corresponded, as far as interior furnishing was concerned, to the discovery of laminated wood, which, compressed in moulds, may equally well be called plastic. In the same way, it is possible for us to relate the appearance of metal construction (the middle of the last century), to the first industrialized furniture of metallic structure. These novelties were at first adopted for commercial furniture or in means of transportation, since these, being directly connected with industrial production, possessed in consequence no feeling of traditional sentiment.

In 1836 Michael Thonet (Germany) began the production of the first piece of furniture from curved wood, later employing the process of curving the wood by fire.

The most notable works of Thonet, in his so called Austrian period, are his rocking chair and the famous “Austrian chairs” which, when exhibited by Le Corbusier in 1925, was declared by him to be “the most economical and the most popular chair in the world.”

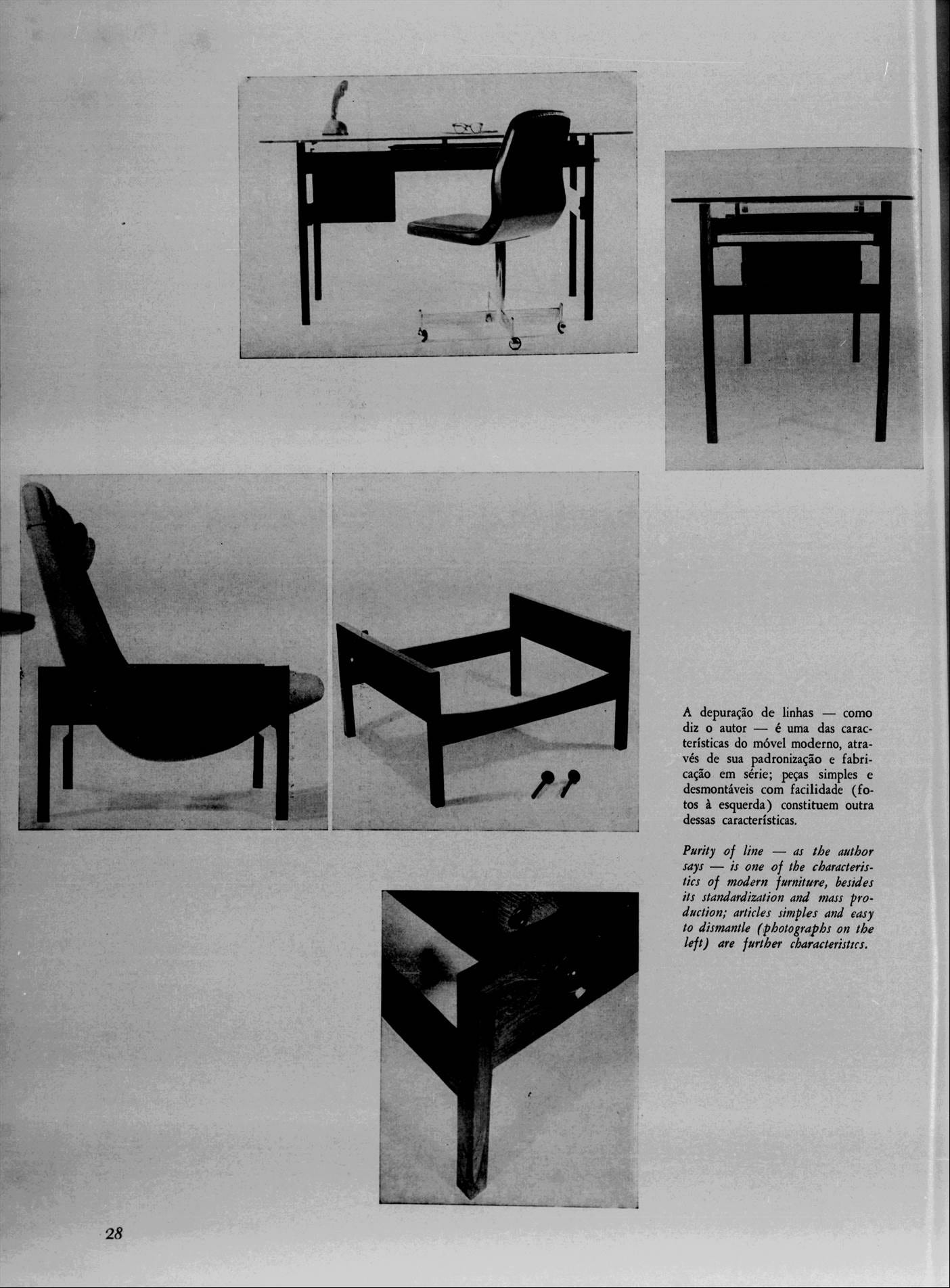

With the “Austrian chair” arose the necessity of special study to facilitate its packing and crating. This demonstrated that apart from the purity of line, pratical considerations had to be taken into account.

Thonet’s productions spread throughout the world and represent the first great mass production of furniture. It is to be observed that the force of tradition was great and that these models, in spite of being made in a manner hitherto unknown, showed an excess of arabesques, which nevertheless failed to take their character from them. These were really the first pieces of modern furniture, for they satisfied the principal demands — comfort, beauty, durability and low cost.

Comfort is the requisite which represents the capacity to satisfy the minimum necessities of the individual, being in short, true functionality.

As to beauty, by no means can such pieces of furniture be called master-pieces’ but for the age, it is undeniable that they represent great advances. Their durability is more than proved, since even today we have examples in use.

The low cost is another of their fundamental characteristics. This is because it was a well organised and directed industry of mass produced furniture in a privileged position, in the middle of Europe, near the source of material (beech forests) and it was thus easy to distribute the chairs to the principal capitals, that were, comparatively speaking, very near.

The industrialization of furniture has permitted an improvement in the standard of living of a great part of the population, who otherwise would never have acquired a work of real craftsmanship. In Brazil we have not yet reached this stage and there are few factories, considering the development of the country, adapted to mass production. Unfortunately they do not process craftsmen specialized in conception and design. Those whom we have are very good draughstmen, playing the part of creators, but who only copy from photographs in foreign magazines, without worrying about proportion, not infrequently modifying or adapting on their own account the masters of industrial design. This problem becomes more grave when the copy is made from Brazilian models, and commercial greed finishes by depreciating, in view of an interior finish, the qualities of the furniture, thus discrediting the honest workman in the eyes of the public. Unhappily, the evil is a result of this phase of evolution, from which we cannot escape, since we are approaching an epoch of great progress.

The craftsman’s work is not within the capacity of all purses, principally because its production is on a small scale and the price of his handiwork very high, not compensating for the use of inferior materials, which after adding up, raises the price of the article considerably. Brazilian architecture owes the position it occupies in the world today to the non-industrialization of the materials of construction, which permits the architect to construct new forms constantly. On the other hand, there have been, and still are few who, to use a familiar phrase, enjoy the advantage of having a house made to measure (craftsmanship), a great part however, being able to possess a fitted one, (craftsmanship — industry). The great majority can only possess a readymade house (industry). At present, with development of the industry in this sphere, standardization is rendering the price more accessible, this being, nevertheless, still far from ideal. These examples in architecture are directly related to furniture.

The discovery of plastics has enormously facilitated the production of pieces of furniture of high aesthetic and functional value at a low cost, bu this happens only in countries of great industrial development, and even there with certain restrictions as regards application, because in the majority of cases the plastic merely replaces the material, the same method of construction being maintained, which completely destroys the value of the work. Plastic is an industrial material par excellence. It can never be used to economic advantage in craftsmanship. This is because plastic requires special moulds, which would considerably raise the cost of production of articles in limited numbers.

The end of the century gave us the “floral” style. Unfortunately, the only fact about it that deserves praise is that it represented a movement in the direction of renovation, escaping from traditional forms.

The experiment, however, was a failure, and the “art nouveau” furniture might perhaps have found a place in a museum. On the other hand, the unpretentious simple and functional line of Thonet has survived the years with general acceptance, forming its own style.

It was only after the First World War that the movement began, and from Thonet we have passed to metallic tube furniture. From the Breuer armchair of 1925 to his elastic chair of 1928. From the S shaped easy chair of Mies Van der Rohe to that of Le Corbusier. Alvar Aalto, by using laminated moulded wood added another characteristic to wood, making it elastic. This discovery marked the decade of ’30. Many other attempts based on the “New Spirit”, but not always so well interpreted, have arisen, from which clumsy solutions have resulted, showing eagerness to simplify surfaces and volumes to the maximum. The most important discovery before the Second World War was that of Eero Saarineen and Charles Eames, who received the prize at a competition organized by the New York Museum of Modern Art. By using special resins, layers of wood and double curved forms, they succeeded in obtaining plastic wood, and in the specimen shown at this museum it is to be noted that the anatomical curves that they previously had succeeded in carving (Windsor chair), are obtained by pressing the special laminated wood in steel mould.

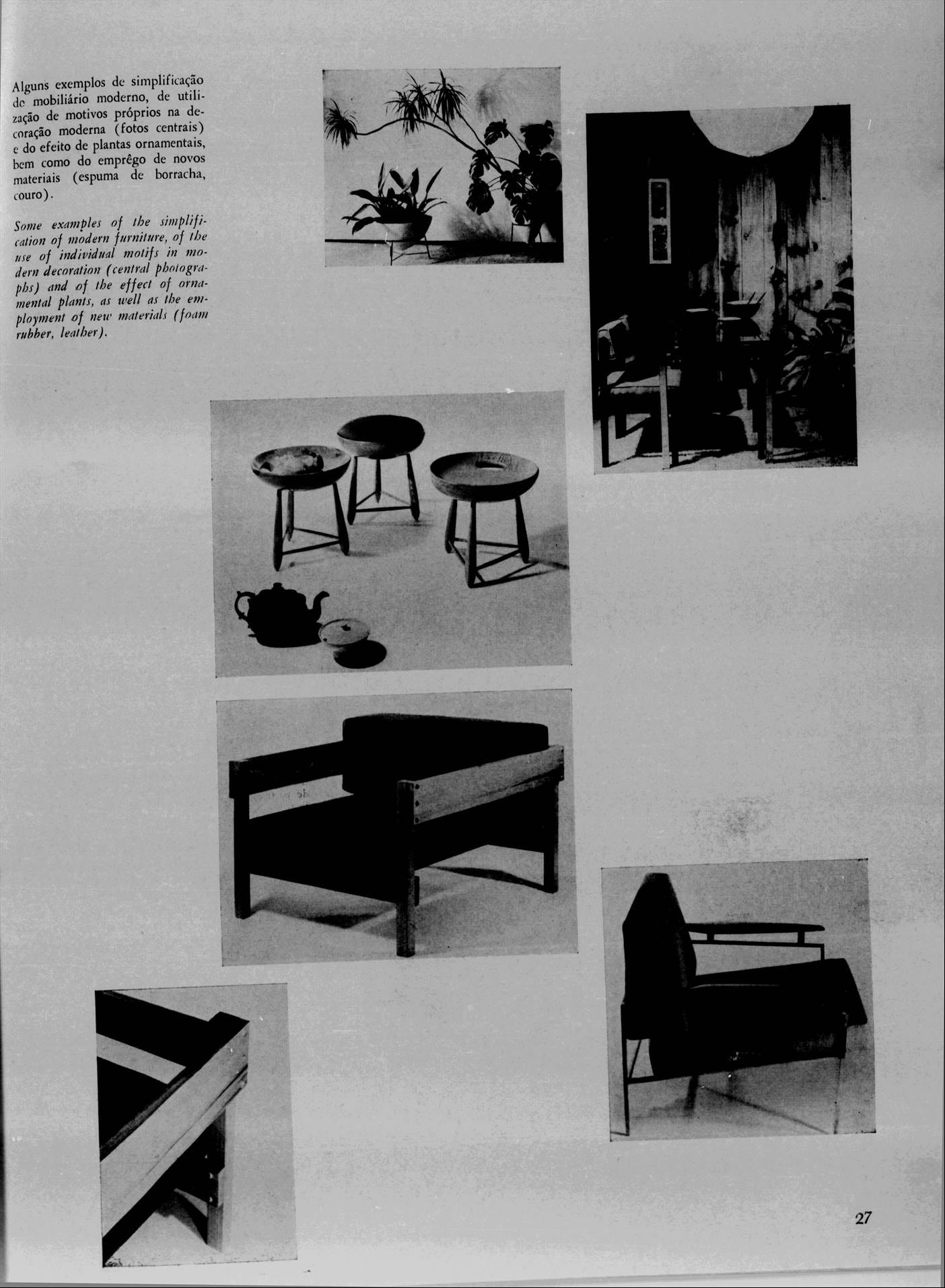

Plastic were developed during the war and only a few years after its end were introduced with success into industry, as were latex sponge and the light alloys perfected by aeronautical engineers. Wood is still the most economical raw material, since only now are plastic factories being set up. In Brazil, where we possess the best kinds of wood, we are continuing without worrying, waiting for the establishment of a plastic industry which will permit us to develop suitable models. Meanwhile, a collection was recently displayed in Rio of prototypes, i.e. articles recently taken from the drawing boards, and which have still do pass through technical and aesthetic perfecting. The sole object was show the efforts we have made in this direction towards making our contribution in the sphere of household equipment. Photographs show clearly the models to which we refer, in wood and metal, special fabrics and leather, as well as sponge rubber (which will go far towards lowering the cost of stuffing), applied in a simple and sincere manner, stressing the constructive system and enhancing the beauty of the material employed.

Modern architecture, like town planning and interior furnishing, tends to unite nations. The interchange of ideias, which for centuries has been difficult, we can now perform at any moment thanks to transport and communication facilities. An article which possesses great aesthetic and technical qualities is featured in the principal magazines of the world, and shown, at international fairs. This permits not only its distribution but also its analysis and perfection. The same thing occurs with new discoveries in industry.

The traditional spirits gradually disappears with time and is replaced by an international one. This has been observed ever since the appearance of the first characteristic articles of modern furniture. Although we have succeeded in prolonging the regional spirit in Brazilian architecture for some time, by using traditional decorations such as ornamental tiles, “combogós” and so on, in the near future the standardization of industry will guide us towards a new target, unifying all such trends.

The traditional note in the future can only be struck by a regional touch, by an object, a piece of furniture, and so forth. The study and appreciation of things relating to regional history are indispensable to the development of a nation. Besides leading the way in new materials the struggle of the architect will be constant to maintain the temper and spirit that our forefathers brought to construction.